MY LIFE AT SEA (THE REREADING SERIES PART 2)

- Douglas Felter

- Feb 8, 2018

- 9 min read

Updated: Jul 14, 2022

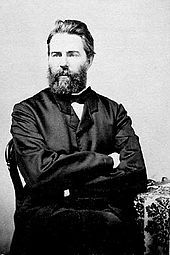

My actual sailing experience is limited to a few excursions on a sailboat on Long Island Sound. I have, however, gone back a few times over the decades to Herman Melville's masterpiece, Moby Dick. It had been a while, though, and I'm not getting any younger, so I thought I would revisit an old friend. I wondered whether the book--possibly the Great American Novel--would stand up to scrutiny at this point in my life, where my curmudgeonly self ("damp, drizzly November in my soul") might take pause. So, I dug in and took the journey (and a journey it is!)

I made sure to read the Bobbs-Merrill annotated edition of the text, long beloved by Melville enthusiasts and long out of print. It was this edition that I first read in junior year in high school, and it took me a while to track down a copy, but that is what eBay is for.

If I get the opportunity to read it again someday, I might go to one of the online annotated versions, such as the one depicted below. I'm guessing it's pretty simple now to explore the many idiosyncratic elements of the book with such guidance.

I was a graduate teaching assistant at my college for two years while I was pursuing my Master's Degree in English, and I must have taught something about Moby Dick to my students, many of whom were older than I was. One of my charges said he had gone to the college library and tried to secure a copy of Melville's novel but to no avail. I had a part-time job in said library and knew the stacks well. I was sure there were dozens of editions of Moby Dick and encouraged him to try again. He came to my office a second time to announce that not only were there no copies of the book available, but that there were no copies of the book at all listed in the card catalogue! I was taken aback but proceeded the next day to head over to the library to see for myself what happened to the Melville section of the library. It was from these shelves that I first experienced The Confidence Man and The Piazza Tales and Bartleby, the Scrivener and Billy Budd. Had a fire incinerated the Melville shelves? But, no, there were dozens, hundreds of copies of Melville masterpieces. There were more copies of Moby Dick than I could have carried to the front desk. When I saw my student the next day, I asked him how he looked up the novel in the card catalogue. He looked at me, straight-faced, and replied confidently, "Why, under Dick, Moby, of course!" Ummm.......

I'm guessing that my first exposure to the novel was either through a Classics Illustrated comic book version: or, the film Moby Dick, directed by the great John Huston and starring Gregory Peck. Since I was a huge Ray Bradbury fan, I discovered that Bradbury had adapted the screenplay for Huston's 1956 film. Therefore, I had to see it. And, to be honest, it is a fairly poetic interpretation of the novel, with some memorable performances by the likes of Richard Basehart and Orson Welles. Peck was miscast as Ahab; he would have been much more appropriate for the first mate, Starbuck, (Yes, that's where the name Starbuck's comes from!) but they needed a star to play the misanthropic captain.

Anyway, I recall my first experience with the novel, one of the most memorable in my high school days and one that still resonates today, a half-century later. My junior English class at Syosset High School was filled with brilliant young minds. Future Pulitzer-Prize Winner Michael Isikoff was in the class, and he wasn't even the dominant presence! Our teacher was 24-year-old Joanne Medioli Tyler--Mrs. Tyler--newly out of college and recently married to another English teacher at our school, the disturbingly handsome and urbane Mr. Tyler.

I'm not going to lie. I "had a little thing" for Mrs. Tyler, and since I wasn't confident enough to think I could win her away from Mr. Tyler by the force of my intelligence alone, I chose to be as entertaining and enthusiastic as it was possible for a 16-year-old to be.

Mrs. Tyler initiated us with something at the beginning of the year--perhaps The Scarlet Letter. But in October, she started us on Melville's chef d'oeuvre. She made the classic mistake of a beginning teacher. She assumed that the book she had loved in college would leave her high school students equally enraptured. So, she taught Moby Dick page-by-page. There was no phrase we didn't explicate, no symbolic strand we didn't attempt to unravel.

I remember that in the back of the room there was a giant, wooden step-ladder, left behind by the maintenance crew. I moved my desk underneath the spread-and-locked ladder and christened the ladder The Pequod, Captain Ahab's ship from Moby Dick. Sometimes I sat on one of the top steps of the ladder ("the crow's nest") during class. Any pathetic way to garner attention I guess.

I did my best to contribute to class daily, keeping up with the ponderous reading load better than most of my classmates managed. I remember one day Mrs. Tyler referred to the "gams" in the book, a term that could refer to a group of whales, but which Melville employed to mean the conversations that took place between sailors from ship to ship when they randomly passed on the high seas. It was a way to convey information before radio. I was the only one who was amused by the word and Mrs. Tyler knew why. She then made sure to ask me why I smiled in front of the class. I explained that I knew the word as slang for a woman's legs, particularly during movies from the 30s when one character might look a beautiful woman up and down and say something like "Get a load of the gams on that babe!" Fortunately, I kept my opinion of Mrs. Tyler's shapely legs to myself.

October ran into November, which ran into December. By Christmas break we were barely half done with the book. We slogged through January and February. We were almost at Chapter 100 of the book's 135 chapters. In March, Mrs. Tyler suggested that the students should teach some of the chapters. My friend Jim Brown waved his hand furiously and volunteered to teach a chapter. Mrs. Tyler agreed. Then Jim said, "Well, I'll only do it if Doug does it." Mrs. Tyler looked to the back of the room for my assent. I nodded. Then Jim said, "Well, Doug has to go first." I was assigned Chapter 99--"The

Doubloon". Captain Ahab had nailed a gold doubloon to the main mast as a reward for whoever spotted the white whale, Moby Dick, first. Symbolism ran amok in this chapter, with each image on the doubloon resonant of themes and motifs that Melville had woven throughout the novel.

I prepared my chapter thoroughly. I decided to dress up in jacket and tie for my first teaching experience. I dragged an attache case out of a closet and put my "lesson plans" inside. I arrived just before the bell, where Mrs. Tyler met me at the entrance to the classroom and got a big kick out of my formal attire. Then...magic. She said my tie was askew and reached out, and (in my memory this is all in super-slo motion), and....straightened it for me! There was a frisson of electricity

and desire that coursed through all of my 130-pound frame as she patted down the newly-aligned tie and said I was ready to go.

I remember drawing the images of the doubloon on the board. I remember Mrs. Tyler sitting with the students. I remember trying really hard to elicit from the students the symbolic import of each image. I remember that most of them hadn't seemed to have read this chapter yet. I remember that Mrs. Tyler was my best student, chiming in when no one else would. But I enjoyed the experience, despite the recollected failure of my lesson. Maybe it wasn't that bad. But I so wanted to impress my teacher, and I felt I had come up short.

As you might have surmised, dear Reader, Jim Brown never taught a lesson. Neither did anyone else. My lesson was a one-off. Maybe Mrs. Tyler deemed it a failure and changed her plans. I like to think she didn't want to embarrass the other students who would have had to have followed me.

A few days later, right after Mrs. Tyler assigned us to read Chapters CIV-CXIII, all hell broke loose. It was just too much. It was March, and we still had a long way to go. Much of the class revolted (it was the Sixties remember) and started shouting at Mrs. Tyler about how bad this whole experience was and how she was at fault for foisting a whale story on us for six months! She burst into tears and rushed out of the room sobbing.

We all looked at each other. I understood the frustration of the students, but I also felt sympathetic to my teacher--a damsel in distress. I suggested that we find her and negotiate a deal. Two other students and I went out independently in search of her. Naturally, as these stories go, I was the one who found her in the book room, head in hands, weeping silently.

She looked up at me, eyes aglaze. There, amid the stacks of Tess of the D'Urbervilles and The Great Gatsby, I softly wiped the tears from her cheeks, gently cupped held her face in my hands, and kissed her swiftly and passionately.

Okay. Maybe that last part didn't happen.

I did, however, say that while the class was sorry for upsetting her, that not everyone was as enthusiastic about Melville's magnum opus as she and I were. I offered a deal. If you come back and start a new book, I said, I guarantee that the class will never bring up the subject again and will act as if nothing ever happened. She agreed and said she would go get cleaned up and be back in a few minutes. I returned to class and compelled my peers to swear they would never mention Moby Dick again. They could finish it if they wanted or not. All pledged to move on. Mrs. Tyler returned, no worse for wear, handed out copies of Ethan Frome, and the white whale was never seen or heard from again.

I, of course, finished reading the book. And I read it again in college. And a couple more times. I remember reading it in the mid-80s when my son was a toddler. One night, after reading to him before his bedtime, I decided that I would read "my book" out loud to him so he could drift off to my baritone. Early in Moby Dick, if memory serves, the protagonist Ishmael asks for the pilot of the Pequod, saying "Where's Bulkington?" My son grew curious. "Where is Bulkington, dad?" For the next couple of days he would look in closets and behind doors and under the couch repeating, "Where's Bulkington?" I don't actually know if he knows any more of the book than that.

Well, it's taken me a while to get to this point, but the book is still one of the greatest works of all literature. Sure, there are lengthy sections about the seemingly infinite uses for whale blubber and the distinctions between a Right Whale and a Bottlenose. And the allusions, especially the religious and scientific ones, can be abstruse, arcane, and esoteric all rolled into one. But the thing is, it's a book that inspires. It makes one think about man's place in the cosmos on the macro level, and man's search into his own heart and soul on the micro level. Its discussions of race and class and ethnicity and creed are all remarkably prescient and insightful. I loved Melville's witticisms, which seemed right on target given our current political climate. The book is replete with refugees and castaways. They are all just looking for a home. "Better to sleep with a sober cannibal than a drunk Christian", says Melville. "Ignorance is the parent of fear" is another line. "I try all things, I achieve what I can," is a third. “Heaven have mercy on us all - Presbyterians and Pagans alike - for we are all somehow dreadfully cracked about the head, and sadly need mending.” The book is filled with such pithy sayings.

Even the most famous opening line suggests man's possibility. The narrator doesn't say, "I am Ishmael" or "My name is Ishmael". He says, "Call me Ishmael". He might as well say, "Call me Doug" or "Call me _______________" (fill in your name here), because Moby Dick is the story of all of us.

The book was so right on target that it destroyed Melville's career. After his earlier works Typee and Omoo made the Best-Seller lists in the 1840s, Melville looked to become one of our country's most successful writers. Moby Dick, and other more demanding works of Melville during the 1850s, scuttled his reputation. By the time he died, his career as a literary artist was largely forgotten. It wasn't until nearly 1920 that critics began to reappraise Melville and his efforts. Now, he is a titanic figure in American literary history, and perhaps Moby Dick can be seen as the singular great work in the American canon. At least it is in the conversation. Can't wait to read it again.